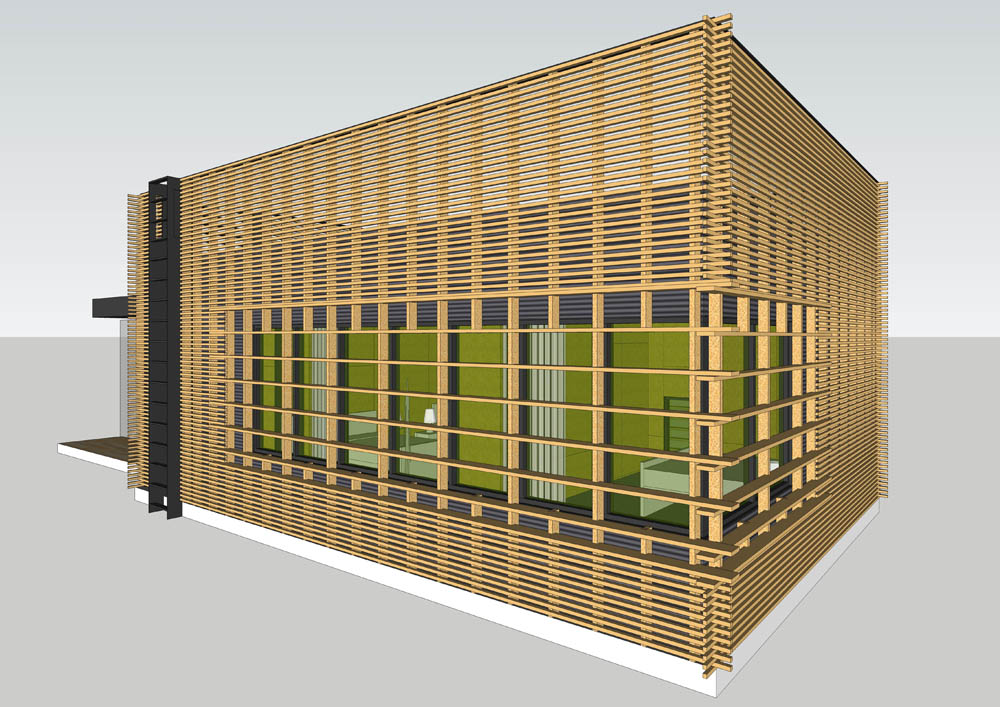

Kids’ Pod v1

Kids’ Pod v1

Painted cement sheet cladding, timber external batten screen, timber framed strip windows, fixed timber louvres to windows, roof deck, steel ladder

What is it?

Our architectural design process at Mihaly Slocombe is pushed and pulled by many forces, though recent self-reflection has made us realise that perhaps no more so than by the opposing pair of conservatism and experimentalism. The conflict between wanting to be like everyone else and be different from everyone else sends powerful currents rippling beneath the surface of every decision we make.

On the one hand, architecture is a serious undertaking. It requires the commitment of very large sums of money and the preparedness of many people – our clients principal among them – to follow our creative vision even though they might not fully understand it. Spending hundreds of thousands (or millions) of dollars on an idea that might not work is not an easy sell. We make safe decisions: use details that have been successful in the past; choose materials that we know will be durable; work with consultants and suppliers that we trust.

This approach is not necessarily negative, indeed it leads to buildings that don’t leak, age well, are timeless. It makes sense to develop a common language through our opus that helps each project learn from the last. To paraphrase something we dimly recall Le Corbusier once said: we try to get the details right so the poetry of our ideas might be experienced unencumbered.

On the other hand, architecture is nothing without risk taking. We can’t live up to our duty as custodians of the built environment without venturing into the unknown. Be it a big idea about sustainable urbanism or a small idea about welded steel door handles, we must constantly search for the new: new possibilities for materials, new opportunities for inhabitation, new strategies for urban density.

Risk taking, together with its first cousin experimentation, involve nutting things out: on paper and in the computer within the studio; then with timber and steel in the factory and on site. It means prototyping options, testing the results, tweaking and testing again. It means evaluating materials and systems with our hands and bodies, understanding them at 1:1 scale. And through it all, it means accepting a certain level of uncertainty: the experiment may work brilliantly or maybe not at all.

Kids’ Pod v1.1

Kids’ Pod v1.1

Corrugated steel cladding, short timber overlap junctions

Kids’ Pod v1.2

Long timber overlap junctions

Kids’ Pod v1.3

Kids’ Pod v1.3

Galvanised steel vertical support battens

Kids’ Pod v1.4

Kids’ Pod v1.4

Timber vertical support battens

Kids’ Pod v1.5

Kids’ Pod v1.5

Green powdercoat painted support frame

Kids’ Pod v1.6

Kids’ Pod v1.6

Shadowline joins at timber ends

Kids’ Pod v1.7

Kids’ Pod v1.7

Overlap joins at timber ends

Kids’ Pod v1.8

Kids’ Pod v1.8

Clear sealed cement sheet cladding

Kids’ Pod v1.9

Kids’ Pod v1.9

Cement sheet cladding continues up to height of balustrade

Kids’ Pod v1.10

Clear sealed cement sheet cladding, black powdercoat painted support frame

Kids’ Pod v1.11

Kids’ Pod v1.11

3x batten spacings to window louvres

Kids’ Pod v1.12

4x batten spacings to window louvres

Kids’ Pod v1.13

5x batten spacings to window louvres

Kids’ Pod v1.14

6x batten spacings to window louvres

What do we think?

The opposite demands of conservatism and experimentalism enjoy an uneasy and ill-defined truce within our architectural practice. It is hard to know sometimes whether or not we are just reinventing the wheel, a necessary individual journey perhaps but hardly experimental, or whether we are truly striking out into new territory.

The analogy of the baker

The architect spends her days working on projects with unique sites, clients, climates, histories, cultures, contexts and regulations. The ever changing matrix of these ingredients demands invention. Her designs are complex and unique, balancing the demands of their ingredients in new and unexpected ways. But are they experimental, or do they merely apply the same rules to different starting conditions?

In contrast, the baker spends her days baking the same, simple loaves of bread: every day, she makes baguettes, cobs and viennas. Experimentation is easy to detect and control here: an extra pinch of flour, a new seed or grain. It is the teacup principle at work, the daily sameness of the baker’s activity makes any change immediately recognisable.

The baker has three important lessons to offer the architect:

- Simplicity. It must always be possible to distil her architecture down to a handful of essential ideas. These ideas drive a project and every decision it demands, from the largest gestures to the smallest details.

- Critical self-awareness. She must understand her own design processes, the what, how and why of her decisions. Then she can begin to differentiate her successes from her failures.

- Restlessness. She must learn to evolve her ideas outside of the specificities of a project. Only when she can distinguish between reinventing the wheel and true experimentation can she be sure she is pursuing the latter.

Kids’ Pod v2.1

Kids’ Pod v2.1

Timber cladding, scissor lift external shutters, hit and miss vertical timber battens

Kids’ Pod v2.2

Kids’ Pod v2.2

CNC routed shiplapped timber lining boards

In his recent Australian lecture tour, Small Projects, Malaysian architect Kevin Low exclaimed gleefully that his own house “leaks like crap”. Before trying something new with a client that might sue or vilify him, he first tries it out on himself. And so, our recent self-reflection has revealed, is the case with us. One of our projects currently under construction and the indirect subject of this article, Kids’ Pod, is for family and so has been the recipient of an unusually high dose of design experimentation.

Our experience of this project has so far been deeply gratifying: relentless design testing in the studio; exhaustive analysis of materials, finishes, junctions and details; collaboration with builder, engineer, craftsman; iterative prototyping in the factory. All of which is only now finding its way onto site.

In the studio, we began with an idea for the identity of the project: a place for grandchildren should be like a supersized cubbyhouse. We sought to embody qualities of robustness, playfulness, theatricality, secrecy, the treetops. We examined every element of the architecture: its programming, siting, proportions, material, fixing, finishing, junctions, span and spacing. We tested materials and interrogated their availability, durability and section sizes; we looked at corner detailing; we investigated the limitations of laser cutting and CNC routing; we examined solar protection options, from fixed louvres to operable shutters. We iterated our design over and over again.

Kids’ Pod v2.2.1

Kids’ Pod v2.2.1

Steel shutter prototype

Kids’ Pod v2.2.2

Kids’ Pod v2.2.2

CNC routed timber prototypes with varied board widths, varied hole sizes, spacings and depths, varied finishes

In the factory, we needed to discover whether our ideas were both possible and affordable. We worked with our builder and metalworker to devise a prototype for an operable shutter system: we tested cladding weight, examined bearing options, shifted stopping tabs by 10mm. We worked with our timber supplier and CNC router to test cladding board widths, holes sizes and positions. We had our painter coat samples of both external cladding and internal linings with various finishes of various gloss levels. We returned to the studio to extrapolate our findings and then went back to the factory once more.

On site, it is all coming together. Kids’ Pod has a slab, wall framing, services rough-in, roof framing and roof cladding. The operable shutters are pinned temporarily in place while we wait for windows to arrive on site. Once installed, cladding boards will be installed, then insulation, internal linings, services fit-off, joinery, finishes.

We have yet to confirm how we will lift the operable shutters: we have ideas, but they have yet to be tested. We will order some components – a cheap boat winch, a couple of electrical switches, some wiring – and see whether they work. Fingers crossed our mathematic equations will permit the shutters to break smoothly open and not bind on themselves. We have yet also to decide on the finish for the timber cladding: do we want it to retain its colour or grey off? We will investigate the best sealers to use to achieve both the former and the latter.

What can we learn?

Architecture is a long game, with development in our ideas and processes leap-frogging across projects that take years to execute. It is tempting for us to err towards conservatism, easy for us to lose sight of the bigger picture. The complacent architect responds by falling on the crutch of familiarity, but the genius manages miraculously to hold onto the trajectory of the bigger picture. It is whispered for instance that Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had only one design idea, which he used for all his projects and evolved carefully across decades.

We can aspire to Mies van der Rohe’s commitment and self-awareness (though perhaps not his myopic focus). In a philosophical sense, this means an abundance of deep thought and self-reflection: a dedication to the long play. Practically, it means establishing the rigour of critique, regular intra- and inter-studio design reviews whose aim it is to draw out the meanings of things.

It also means a commitment to research and experimentation: architecture exists at the intersection of ideas and making. These realms collide in all sorts of interesting ways, both limiting and accelerating the other. A thought on paper is just as easily resolved as hindered by the exigencies of craft. It’s only when we put them together, shift from the representation of the thing to the thing itself, the architecture, that we can find out whether or not our ideas will work. And so it comes back to risk taking and the value of experimentation.

We guess it’s not called architecture practice for nothing.

Fantastic post, one of your best!

Thanks, Michael. I appreciate it.

Very interesting article. Can’t imagine how many hours of hard work do you spend on one project.

Hundreds typically, often well over a thousand. We track all our hours, but sometimes it’s best not to look!